Operation Lifeline: A mission to change and save lives

More than half of our British armed forces heroes struggle with mental and physical health issues when they leave the service.

Some are so traumatised that they go on to take their own lives.

The number of veterans coming forward for help is surging, but so many more are still hiding in the shadows.

We need to find them and support them into recovery. The clock is ticking and every second counts.

Operation Lifeline is a mission to end mental health suffering and reduce suicide.

This is our biggest ever campaign, with an aim to raise £6 million per year - Operation Lifeline will fund life-changing and life-saving therapy, counselling and support all over the UK.

Thanks to donations and players of the Veterans' Lottery, Operation Lifeline is already underway - some veterans have started their journey of rehabilitation - but it isn't enough.

If you want to play your part in Operation Lifeline, there is a way you can make an immediate impact.

But before you make that step, please watch this short film from veterans, and their families, explaining the battles they have faced and why they need your help.

Watch now: Why Operation Lifeline will change lives and save lives

Content warning: this film contains references to mental health and suicide.

Sponsor A Veteran - why our veterans urgently need your help

Thousands of veterans across Britain are fighting a daily battle with combat trauma and are in urgent need of help.

Many more veterans, damaged by what they lived through during service, are struggling in silence.

When you Sponsor A Veteran through Operation Lifeline you change a world. Your support provides:

- The very best one-to-one professional counselling and hope that the invisible scars of service can be healed – it is the start of a journey of recovery.

- Vital 24/7 telephone helplines for our armed forces and veterans at the lowest of moments.

- Support dogs as well as access to wellbeing activities where veterans heal together - group therapy can be crucial to recovery.

- Research into PTSD to find better treatments and help for our armed forces and veterans.

- New hope for our heroes in need and a reduction in suicide rates in the armed forces and veterans community.

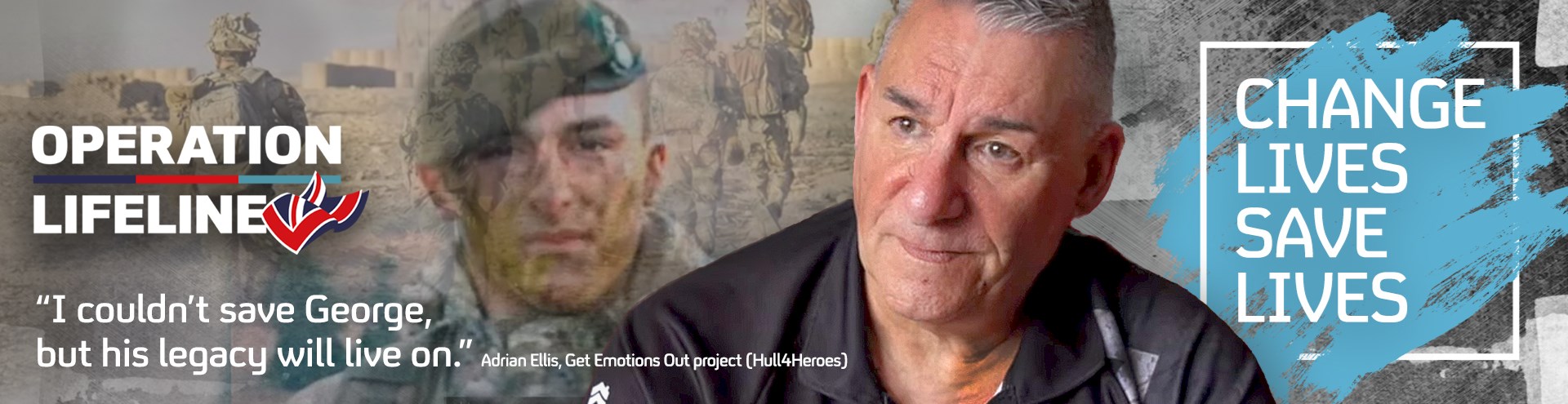

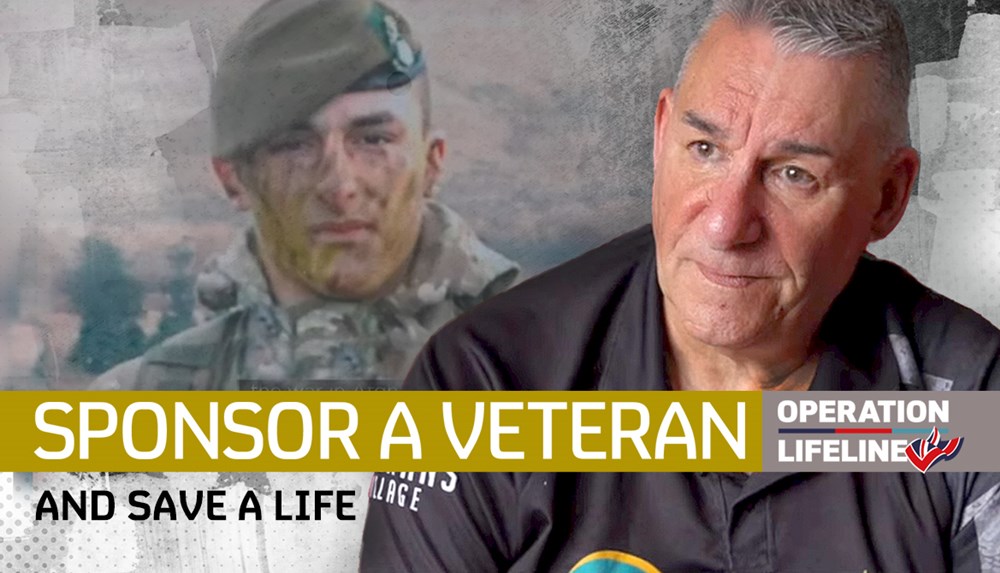

"I wasn't able to save my son, George, but Operation Lifeline will help mental health projects like GEO. His legacy will live on through helping veterans combat their personal battles," Adrian Ellis, Get Emotions Out

What do sponsors receive?

Once signed up, your impact on a veteran's life begins straight away. We know that every moment matters for those in need.

Every month, veterans that you are helping will share their journey of recovery. You'll learn more about how Sponsor A Veteran is rebuilding their life.

You will also be provided with regular updates from the charities across the country that are delivering this life-changing work on your behalf.

And not only that, you will also receive an Operation Lifeline lapel badge in recognition of your sponsorship support. Please wear it with pride - you are part of a very special support network.

Sign up

When a veteran begins their rehabilitation, it is a journey that can be complex and emotional. Support for those with PTSD can take time.

For that reason we ask you to maintain your monthly sponsorship for as long as you are able.

On behalf of our British veterans, and their families, thank you.

Real life stories - the truth about mental health in our armed forces

In 2021, 253 UK veterans took their own lives.

George Ellis was one of them. He was just 24.

George served six years with the Yorkshire Regiment 1 Yorks. In late April, George took his own life.

Since that devastating moment, his father, Adrian, has campaigned to raise awareness around suicide in young people and helped to set up a talking group that supports veterans with mental health issues.

“George wanted to join the Army, it was the right thing for him to do and the proudest day of my life was watching him pass out," said Adrian.

"The colleagues we’ve spoken to said he was such an amazing soldier and the guy that would lift them when they were down.

"When he came out of the Army after six years, having served in Afghanistan, George struggled to adapt," he added.

"Civilian life was so different and it was a culture shock."

“He then met Katie, his girlfriend, and he was a different George. He blossomed," said Adrian.

But at 8.31pm on Friday, April 30, 2021, Adrian, who was away from home at the time, received a text message.

It read: 'Dad, where’s the tablets, I’m going to kill myself. I‘m sorry, I love you.'

By the time Adrian and his wife Carol returned, George had passed away.

“After we lost George I was beating myself up. Maybe like survivor’s guilt. Why has my son done this? What was so bad that he took his own life, why couldn’t he reach out?

“Someone once told me it gets better with time, my answer to that would be grief never goes away,” said Adrian.

It was then that Paul Matson, founder of Hull 4 Heroes, contacted George with a view to setting up military mens’ talking group so veterans could meet and discuss their problems. Soon after, GEO was born.

GEO didn’t just stand for Get Emotions Out, it was George Ellis’ nickname, too.

“The veterans have all said they go to the doctors but the doctors don’t know how to treat them. But they feel at home in this GEO environment," explained Adrian.

“We have had people attend GEO with a plan to end their life and they’ve come back the next week and they’ve torn that plan up. They are in a room with people who understand and that’s so powerful.

“I couldn’t save George but his legacy will live on.”

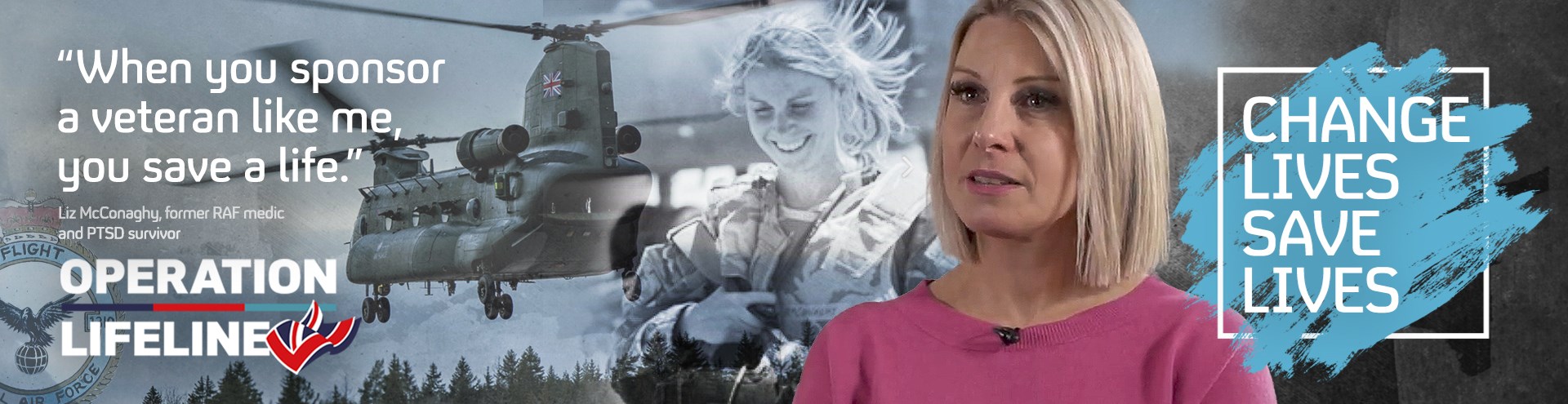

Hi, my name’s Liz and I was a member of the RAF’s Medical Emergency Response Team (MERT). This is my story, thank you for reading it.

At the age of 21, I was on the frontline in Helmand Province, dropping into war zones in a Chinook helicopter to support British casualties.

I was deployed for ten highly kinetic tours and flew over 3,000 hours until being finally discharged due to a neck injury.

Without the uniform and the sense of identity it provided, life became very challenging and what I had gone through being part of the response team took its toll.

In August 2020, I attempted to end my life by taking an overdose.

I’ve asked myself, what made me do it, what made me want to end my life?

The main trigger can be tracked back to a night when I couldn't sleep. I started looking up the back catalogue of the soldiers that I picked up on MERT who had died.

Those memories really started to fester in my head, and it was filled with random thoughts that I just couldn't get rid of.

At the time, I always used to look at the casualties, and the bodies that we picked up on MERT, as just a really precious piece of freight because if I started to humanise them then that really would have been the start of the undoing of me.

I think a lot of us felt the same.

My busiest day of service involved 14 back-to-back missions, retrieving injured troops and bodies. The effort and sacrifices made in Afghanistan significantly advanced medical science and that gave me a real sense of purpose.

But when I was medically discharged, I lost my identity. I felt invisible. Lost. It is something many veterans battle with.

The 2020 lockdown further unravelled my mental state and in August, I attempted to take my own life with an overdose. Thankfully I failed.

I woke up in intensive care two days later and my mental state had completely shifted; I didn't want to die.

Thanks to the veterans support system, which has been vital to my survival, I am rebuilding my life. Sadly some veterans haven’t been as lucky as me.

If you really want to help, and play a part in rebuilding a life, then please support Operation Lifeline and Sponsor A Veteran.

There are thousands of veterans waiting to begin their journey of recovery – waiting for the chance to live a full life again. Your sponsorship will make that happen.

If you are affected by the topics in this content, urgent help is available through services like the Samaritans (116 123), or the Crisis Text Line (text 'SHOUT' to 85258).